Indirect Land Use Impacts of Biofuels

Can we reduce greenhouse gases with biofuels? Explore biofuels, the carbon cycle and potential impacts.

Table of Contents

Biofuels and the Carbon Cycle

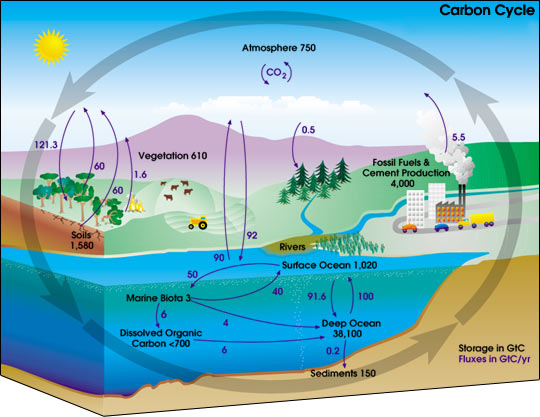

From the standpoint of human-released carbon dioxide, other greenhouse gas emissions, and contributions to climate change biofuels have one large advantage over gasoline, diesel and other fossil fuels: The feedstocks for biofuels are part of the above-ground carbon cycle. Unlike petroleum or coal, the soybeans, corn,switchgrass and other biological materials that are made into biofuels are not dug up from underground, nor do they release long-stored carbon as carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when burned. Instead, when biofuels are burned, carbon dioxide they recently captured is release back into the atmosphere.

This advantage has sometimes been exaggerated into the claim that biodiesel, ethanol and other biofuels are carbon neutral.Unfortunately, this is not always true. For example, fossil fuels that release carbon dioxide are used in farming, fertilizer production, transportation and many aspects of biofuel processing during the full life cycle of most biofuels.

Indirect Land Use Impacts of Biofuels

Cropping changes, the conversion of forests into cropland and other land-use changes connected with the growing of biofuel crops all have greenhouse gas, and thus climate change implications. Worldwide land-use patterns can be affected by small variations in commodity prices, and these effects need to be considered in a full life-cycle analysis.

Two articles in the February 2008 issue of the journal Science called widespread attention to these so-called indirect land use impacts of biofuels. (See Fargione et al, 2008 and Searchinger et al, 2008.)

The study of indirect land-use impacts is in its infancy, and predictions and measurements of these impacts are highly uncertain. Biotech companies and others have claimed that crop yield improvements will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by making farmland more productive, meeting the world’s food and fuel needs with fewer acres, and reducing pressure to convert forests to farmland. In an ideal world this might all be true. But in the real world, land use change is driven by complex economic, social and political forces. Productivity is only one factor.

Differences among Biofuels

Various efforts have begun to evaluate the sustainability of biofuel production systems. For example, some groups are working to create third-party certification standards, reflecting a growing awareness that there are great differences among the greenhouse gas footprints and other environmental and social impacts of biofuels. In one extreme and widely publicized example, the clearing and burning of rainforests for oil palm plantations in Indonesia is alleged to have caused enormous releases of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases as well as other serious environmental problems. At the other end of the spectrum, fuel made from waste vegetable oil or spoiled grain typically causes few concerns.

Estimating the net effect of any given biofuel on atmospheric greenhouse gas levels or climate change requires extremely complicated calculations with many debatable assumptions. Many of the analyses to date have concluded that grain ethanol, biodiesel, and especially cellulosic ethanol substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions, in comparison to gasoline and diesel. Other researchers have called these results into question, however. (See, for example, Pimentel and Patzek, 2005.) Despite these different views, it is clear that biofuels are most likely to contribute to greenhouse gas reductions if they are produced with a minimum of fossil energy inputs and without significant land use changes.